Featured

Women’s Rights in the MENA Region: Progress & Obstacles

Published

3 years agoon

A Background to Women’s Rights in the MENA Region

Gender equality is a fundamental human right and an imperative foundation which lays the groundwork for a peaceful, prosperous and sustainable world. The development of women’s rights in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region has seen much progress and obstacles over the past decade. However, the unequal status of women stands out as a particularly challenging problem.

Following “International Women’s Day” last month, this article provides a snapshot of the development of women’s rights in the MENA region as of April 2023. MENA countries include Algeria, Bahrain, Egypt, Iran, Iraq, Israel, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Libya, Morocco, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Syria, Tunisia, United Arab Emirates and Yemen.

The MENA region has a reputation for struggling with gender equality. Therefore, this article focuses on this region. However, it is important to emphasize that the MENA region is not the only place women experience inequality. Gender inequality is also seen in Asia, Africa, Latin America, Europe, and North America. Undoubtedly, women continue to face discrimination and significant barriers to fully realizing their rights worldwide.

Any Progress in the MENA Region?

Governments are developing stronger laws and policies to support women’s rights.

Significant laws, policies, and programming developments have focused on gender equality within the MENA region. Moreover, women’s representation in government has increased.

Many countries in the region have established “national women’s machinery”. This machinery is used in government offices, departments, commissions, or ministries. All these provide government leadership and support in achieving gender equality.

Furthermore, there have been notable improvements in education and health within gender-related indices. There has been an increase in specialized programming to support women’s rights and empowerment in this region.

Women struggle to uphold their rights in places like Palestine. It is international human rights laws and conventions which are helping women in advocating for and strengthening their fight. Since the ratification of the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) by the State of Palestine in March 2014, civil society organizations and women human rights defenders have publicly advocated for the implementation of the Convention and the passing of a Family Protection Bill, pending since the early 2000s, which would specifically address gender-based discrimination and violence. In turn, this will help to edge women closer towards gender equality in the occupied Palestinian territory.

Women are increasing their role in civil society and advocating their rights

Women are increasing their engagement in civil society. Women’s and youth feminist civil society has started to dominate the political scene in advocating for and securing gains. In Iran, millions of young women took to the street following Mahsa Amini’s death in police custody for improperly wearing her hijab. These women risked their lives to change the system. Many were arrested and beaten and now face the death penalty for speaking out. This demonstrates women’s power in standing up against authoritarian regimes and fighting oppression.

The Iranian government is brutally repressing women’s voices who courageously stand up for their freedom. The UN has called Iran a “gender apartheid” on women.

Read more: Mahsa Amini: Iranian Women Are Leading an Extraordinary Revolution.

Women’s civil society actively engages internationally with the “Women’s Peace and Security” agenda. Remarkably, women activists have testified before the United Nations Security Council. The UN Women highlighted the gender impact of conflict and occupation on women’s rights.

What Obstacles Hinder the Development of Women’s Rights in the MENA Region?

Women face many inequalities within the MENA society, correlating them as second-class citizens with little to no protection from violence. The COVID-19 pandemic has compounded existing inequalities. Moreover, factors significantly reducing space for constructive civil society engagement with governments include ongoing conflict, the revival of extremist religious groups, and increased political turmoil. These international crises created many setbacks in passing long-term legal change.

Poverty & gender-based violence

The 2022 global poverty update from the World Bank reports that the MENA region is the only place worldwide where the extreme poverty rate increased between 2010 and 2020. Poverty has a detrimental impact on women’s rights.

Gender-based violence is also one of the main challenges facing women in the region today, with devastating effects on their health and well-being and their economic and civic participation.

Read more: Female Genital Mutilation in Somalia Reflects Deep-Rooted Gender Inequality.

A striking example of gender-based violence was in 2022 when the Israeli forces shot dead Al Jazeera’s journalist Shireen Abu Akleh in the occupied West Bank. Abu Akleh, a longtime TV correspondent for Al Jazeera Arabic, was killed on the 11th of May 2022 while covering Israeli army raids in Jenin in the northern occupied West Bank.

Read more: Who is Shireen Abu Akleh?

Women have no right to nationality in the MENA region

The MENA region has the highest concentration of gender-discriminatory nationality laws. An estimated 50% of the 25 countries in MENA deny women equal rights to pass nationality to their children.

Algeria is the only country in the region with nationality laws upholding complete gender equality, including women’s right to confer nationality on their children and noncitizen spouse on an equal basis with men. Thus, gender discrimination in nationality laws is one of the primary causes of statelessness in the MENA region, in addition to causing several other human rights violations.

Lebanon, Kuwait, and Qatar deny women the right to confer nationality to their children and spouses in all circumstances. Other States, including Bahrain, Jordan, Libya, Oman, Saudi Arabia, Syria and the United Arab Emirates (UAE), deny women the right to confer their nationality to children in most circumstances.

Read more: World Leaders Remain Silent Over Human Rights Violations in the UAE.

Malnutrition in women and girls increases by 25%

Malnutrition in women and girls increased by 25% in crisis-hit countries in the MENA region between 2020-2022. Over a billion women and adolescent girls are malnourished in the world. This has detrimental health, economic and well-being impacts. Most women and girls affected by this statistic live in the MENA region. Both local and global crises in 2023 could exacerbate the development of women and girls living there. Rising poverty and inequities increase the chances that people will turn to cheap, ultra-processed, unhealthy foods.

“Addressing malnutrition in women and girls is essential to reduce the gender health gap”

Amira Ghouaibi, Project Lead, Women’s Health Initiative, Shaping the Future of Health and Healthcare, World Economic Forum.

Therefore, the world is making slow progress. Issues like soaring food prices, climate change and the lasting impact of the COVID-19 pandemic risk making the nutrition crisis an even more significant problem in 2023. Nutrition is a widely overlooked issue; coordinated access and policy intervention are urgently needed.

Read more: Children’s Rights in Yemen Are Teetering on the Edge of A Catastrophe.

Survey Findings Provide Unprecedented Insights into Gender Attitudes in MENA Region

Despite incremental progress and the advancements mentioned above, gender attitudes across the region continue to fall behind internationally recognized standards.

The opinions and attitudes of citizens across the MENA region were recorded in the latest Arab Barometer survey from October 2021 to July 2022. This is the largest publically available survey published since the onset of COVID. Its results were shocking across 12 MENA countries, which collectively are home to 80 per cent of the citizen population in the Arab world. The findings give an unprecedented insight into the everyday lives of these citizens.

The survey showed a plurality of citizens either agree or strongly agree with the following statement:

“In general, men are better at political leadership than women.”

More than three-quarters of Algerians (76%) support this view, as do majorities of respondents in:

- Libya (69%),

- Iraq (69%),

- Jordan (66%),

- Egypt (66%),

- Palestine (65%), and

- Kuwait (65%).

Surprisingly, only in Lebanon and Tunisia do most of the population disagree or strongly disagree with the above statement.

Moreover, governments’ patriarchal character has effectively prevented efforts to address negative cultural and social constructs against women meaningfully. This limits the ability to change prevailing gender power relations and social roles qualitatively.

Concluding Thoughts

The development of women’s rights in the MENA region remains unresolved.

It does not reflect the commitments to the Agenda 2030 and the Sustainable Development Goals. Incremental progress has been documented, yet the pace is slow. Recent survey results showing gender discriminatory ideologies across the region show we still have much work to do to educate developing countries on gender equality.

Gender-based violence, lack of equal opportunities for economic activities or fundamental rights, and deprivation from political participation and representation have been the challenges facing this region.

Women are rising across the MENA region and fighting for their rights to be heard and implemented. Remarkably, women are igniting a powerful revolution against many corrupt governments, and their strength and courage are both admirable and breathtaking.

You may like

-

Mahsa Amini: Iranian Women Are Leading an Extraordinary Revolution

-

Pakistan’s Climate Crisis: A Peek Into The Apocalyptic Future That Awaits

-

World Leaders Remain Silent Over Human Rights Violations in the UAE

-

US Supreme Court Overruled Constitutional Guarantee of Abortion Access in Roe v Wade

-

Female Genital Mutilation in Somalia Reflects Deep-Rooted Gender Inequality

-

Roe v Wade: US Supreme Court Ruling Could Imperil Women’s Abortion Rights Around the World

Featured

Board of Peace Explained: New Global Peace Architecture or Another Power Play?

Published

5 days agoon

January 19, 2026

This is not just about a region in this world where human rights are not given, and people are being killed. It is about humanity, life, and the very foundations of values that humans are living with. When Gaza is discussed today, it is rarely in the language of rights. It is discussed as a problem to be solved, a territory to be stabilized, and a population to be administered.

The announcement of a new international “Board of Peace” fits neatly into this pattern. Presented as a bold initiative to guide Gaza out of conflict and into reconstruction, the Board of Peace has been framed by its sponsors as innovative, inclusive, and forward-looking. Yet for Palestinians, the announcement raises an older, still unresolved question: Who decides Gaza’s future, and on what authority?

What Is the Board of Peace?

The Board of Peace was announced by US President Donald Trump as part of a broader Phase Two Gaza plan, marking a shift from ceasefire management to post-genocide governance and reconstruction.

According to official descriptions, the board is meant to:

- Oversee Gaza’s political transition

- Coordinate reconstruction funding and investment

- Provide international supervision during a “transitional” period

Trump declared himself chair of the board and described it as a high-level body composed of political leaders, financial figures, and diplomatic actors. Unlike the United Nations, the board has no clear treaty basis, no General Assembly mandate, and no defined accountability mechanism.

It is powerful not because it is formal, but because it is backed by money, political leverage, and security control.

Who is on the Board?

The individuals named or referenced in connection with the Board of Peace are not neutral facilitators.

The board’s executive circle includes:

- Marco Rubio, US Senator and the Secretary of State

- Tony Blair, former UK prime minister

- Jared Kushner, Trump’s son-in-law and former Middle East envoy

- Steve Witkoff, US real estate magnate and political donor

- Ajay Banga, President of the World Bank

These are figures associated with Western political power, financial institutions, and security-centric diplomacy. None are elected Palestinian representatives. None comes from Gaza. The imbalance is structural, not incidental.

Which Countries Were Invited?

One of the board’s defining features is its attempt to project global legitimacy through invited state participation.

According to credible sources, Trump sent invitations to around 60 world leaders. Those explicitly named in reporting include:

- Turkey (President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan)

- Egypt (President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi)

- Canada (Prime Minister Mark Carney)

- Argentina (President Javier Milei)

Moreover, some diplomatic sources also indicate the list includes:

- Britain

- Germany

- Italy

- Morocco

- Indonesia

- Australia

The Palestinian Face of the Plan: Who Is Ali Shaath?

To provide the plan with Palestinian leadership, the US has backed Ali Shaath as head of the transitional Palestinian committee that will administer Gaza’s civil affairs under the Board of Peace.

Shaath’s profile is central to understanding how this governance model is being sold.

Here is a quick overview of Ali Shaath:

- He was born in 1958 in Khan Younis

- He is a civil engineer with a PhD from Queen’s University Belfast

- He previously served as deputy minister of planning in the Palestinian Authority

- He has worked on industrial zone projects in both Gaza and the West Bank

Shaath has spoken publicly about the scale of Gaza’s destruction, estimating around 68 million tons of rubble, much of it contaminated with unexploded ordnance. He has suggested that clearing debris could take three years, with full recovery achievable in seven years. It seems to be a far more optimistic timeline than UN estimates, which warn that rebuilding could extend beyond 2040.

Politically, Shaath has been described as acceptable to both Hamas and Palestinian Authority President Mahmoud Abbas, precisely because he is positioned as a technocrat rather than a political leader. However, it is yet to be observed how he would work with the other members.

Governance Without Sovereignty

The Palestinian committee, chaired by Shaath, has issued a mission statement pledging to restore services, rebuild infrastructure, and stabilize daily life in Gaza.

The committee describes its work as “rooted in peace” and focused on technocratic administration rather than politics.

Yet the committee:

- Controls no borders

- Commands no security forces

- Regulates no airspace or coastline

- Has no electoral mandate

It governs without power, while power remains in external hands.

When it comes to the reaction of the people of Gaza, they showed mixed feelings of skepticism over hope. Some Palestinians express cautious hope that any plan might bring electricity, water, and an end to constant displacement. Others see the Board of Peace as another externally designed structure that manages Gaza without addressing the occupation.

Peace Architecture or Power Management?

The Board of Peace is being presented as an innovation. However, history offers a cautionary lens.

Temporary governance structures in occupied or post-conflict territories have a habit of becoming permanent. Reconstruction becomes conditional. Aid becomes leverage. Administration replaces self-determination.

In a nutshell, the Board of Peace asks the world to believe that stability can precede justice, and that governance can substitute for freedom.

For Palestinians, the unanswered question is simpler and older:

If Gaza’s future is designed in Washington, financed in global capitals, and overseen by external boards—where does Palestinian self-determination actually begin?

Until that question is addressed, the Board of Peace risks becoming not a new architecture for peace, but another structure built on the same imbalance that has kept Gaza unfree for decades.

Peace cannot be outsourced, and a people cannot be rebuilt while being brutally ruled.

Featured

Phase Two of Gaza’s Plan: Demilitarization, Technocracy, and a Ceasefire That Still Bleeds

Published

5 days agoon

January 19, 2026

The second phase of Gaza’s so-called peace plan has officially been announced. It is being described as a transition from ceasefire to governance, from violence to rebuilding. However, on the ground in Gaza, the distinction is harder to locate.

Isn’t it shocking that more than three months after the ceasefire took effect in October, Palestinians are still being killed, and aid is a privilege to have? Entire neighborhoods remain uninhabitable. So, the announcement of phase two does not coincide with calm. It arrives amid continued military pressure, delayed withdrawals, and a humanitarian system operating far below what was promised.

There is a crucial question Palestinians are asking, and that is not whether Phase Two exists on paper, but whether it alters the reality of power.

What Phase Two Claims to Change

According to some US officials, Phase Two is meant to shift the Gaza file from emergency truce management to long-term stabilization. Its three pillars are clear:

- First, the demilitarization of Hamas and other armed groups, framed as a non-negotiable precondition for any durable peace.

- Second, the establishment of a Palestinian technocratic committee to administer Gaza’s civil affairs during a transitional period.

- Third, the beginning of reconstruction planning, coordinated under international supervision and tied to security compliance.

In theory, this is where genocide ends, and governance begins, but in practice, each pillar raises more questions than answers.

Phase One by the Numbers: A Ceasefire in Name

Before moving further, let’s have a look at the overview of Phase One. Since the ceasefire came into force on October 10, at least 451 Palestinians have been killed and more than 1,250 injured, an average of nearly five deaths per day. Military operations continued under the language of “enforcement” and “targeted action,” blurring the very meaning of a ceasefire.

When it comes to the prisoner exchanges, Hamas and Israel both released most of the captives. Bodies were also exchanged, with one reportedly still trapped under rubble.

Aid delivery fell far short of commitments. Between October and early January, around 23,019 aid trucks entered Gaza out of a promised 54,000, roughly 43% of the target.

Critical crossings, including Rafah, remained closed or heavily restricted. Aid organizations reported operational paralysis as bans, inspections, and suspensions multiplied.

In other words, Phase One did not fulfill its promises. It managed the violence without ending it.

Demilitarization Before Relief

Phase Two places demilitarization at its core. President Trump has repeatedly framed it as a binary choice—an “easy way or a hard way.” The message is unambiguous: disarmament first, normalization later.

What remains unaddressed is the imbalance this creates. Israel retains control over Gaza’s airspace, coastline, borders, population registry, and imports. Palestinian armed groups are asked to disarm while occupation-level controls persist.

It is pertinent to mention that international law does not recognize demilitarization as a substitute for political rights. Yet phase two calls itself the engine of peace, while humanitarian access, withdrawal timelines, and accountability for genocidal destruction remain secondary.

For many Palestinians, this sequencing feels less like peacebuilding and more like containment.

The Technocratic Committee: Governance Without Power

There will be a 15-member Palestinian committee tasked with administering Gaza’s civil affairs. Its stated mission includes restoring basic services, managing reconstruction, and laying foundations for stability.

Its members are presented as non-political professionals, including engineers, administrators, and planners. But what is missing is authority.

The committee operates under external oversight, with no electoral mandate, no independent security control, and no ability to regulate borders, trade, or movement. Its legitimacy is managerial, not democratic.

However, it’s not shocking for Palestinians as they are familiar with this model. Over the past three decades, “temporary” arrangements have repeatedly substituted administration for sovereignty. Technocracy becomes a way to manage populations without resolving the structures that disempower them.

Palestinian Voices

Some reports from Gaza capture a mood that is neither celebratory nor dismissive, but only exhausted.

Some residents express cautious hope that Phase Two might at least bring predictability: electricity that lasts more than a few hours, water that runs clean, streets cleared of rubble. On the other hand, most of them see another externally designed plan that speaks the language of peace while preserving the architecture of control.

One displaced man described being forced to move 17 times since the genocide began. Another questioned how demilitarization could be discussed while entire families still sleep in tents beside the ruins of their homes.

For many, peace is not an abstract framework, but the ability to survive the night without fear.

Aid as Leverage, Reconstruction as Reward

Phase Two introduces reconstruction, but not as a right. Aid and rebuilding are explicitly linked to compliance. This conditionality transforms humanitarian relief into a pressure tool.

History offers little comfort here. Millions pledged to Gaza after previous acts were delayed, diverted, or blocked entirely. The difference now is scale. Gaza’s destruction is unprecedented, with tens of millions of tons of rubble, unexploded ordnance, and erased neighborhoods.

Therefore, rebuilding without political change risks entrenching dependency rather than restoring dignity.

A Governance Phase Built on Unresolved Violence

Although phase two is described as a transition, transitions require movement—away from violence, toward rights.

So far, what has changed is not the structure of power, but the language used to describe it.

Demilitarization is demanded without de-occupation. Governance is promised without sovereignty. Reconstruction is discussed while restrictions remain.

This is not peace delayed. It is peace redefined—away from justice, toward management. Ultimately, nothing can substitute for Gaza’s right to determine its own future, which has been denied for decades.

When governments talk about protecting children, their words rarely match what young Palestinians are living through. In the Gaza Strip, education is not merely disrupted; it is being systematically erased, leaving the possibility of a generation without basic schooling and awareness.

A recent analysis done by the University of California warned that children in Gaza may lose the equivalent of five years of education due to repeated school closures since 2020. These conditions are compounded by violence, trauma, and chronic destruction of infrastructure.

Almost all of the schools have been partially or completely destroyed by Israel. If schools remain out of session until at least 2027, many teenagers will be a decade behind where they should be educationally.

This is not only about education but the erasure of an entire generation, coupled with despair. It is ultimately the humanitarian consequence of genocide-scale violence and blockade. The future is being stolen from innocent lives, and the world is witnessing one of the greatest catastrophes in the history of mankind.

The Scale of the Education Collapse in Gaza

Before the genocide intensified, Gaza had an education system serving nearly 660,000 school-aged children. However, two years of bombardment, destruction, and blockade have devastated this system:

- An estimated 97% of schools in Gaza are damaged or destroyed.

- Hundreds of thousands of children have had little to no access to face-to-face schooling for more than two academic years.

- More than 18,000 students and 780 teachers were killed as of October 2025, according to UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) data included in international analysis, representing a massive depletion of both students and educators.

- UNRWA reported that around 660,000 children are out of school, with many classrooms repurposed as shelters for displaced families.

These figures combine lost school buildings with lost lives and lost opportunities. These conditions are creating structural barriers to learning that go far beyond temporary closures.

What It Means to Lose Years of Education

According to the Cambridge analysis, repeated closures since 2020, first due to the pandemic and then to ongoing genocide, have eroded more years of learning than children can realistically recover.

This isn’t just falling behind, but a fundamental derailment of life trajectory:

- Delayed literacy and numeracy milestones

- Increased likelihood of dropout in teenage years

- Higher risks of early marriage and child labor

- Limited access to higher education and careers

Resultantly, when education stops, social mobility also stops with it.

Education as a Protective Space

Children’s access to education is not just about reading and math, but about safety, structure, and psychological stability.

UNICEF and other child protection agencies have emphasized that education provides:

- Protection from exploitation and abuse

- Psychosocial support

- A routine that counteracts trauma

- Opportunities for social interaction and identity building

When schools are reduced to rubble or become temporary shelters, these protective functions disappear. Instead, Gaza’s schools increasingly resemble sites of trauma, displacement, and interruption, not growth.

Trauma, Hunger, and Learning Loss: A Spiral of Harm

The education crisis in Gaza does not exist in isolation, but it intersects with:

- Widespread hunger and malnutrition, which impair cognitive development

- Psychological trauma, which reduces concentration and memory

- Displacement and instability, which make regular attendance impossible

A recent scientific analysis describes how children exposed to conflict, displacement, and trauma face long-term developmental challenges, including reduced educational outcomes.

Comparing Gaza to Global Conflict Patterns

Gaza’s education collapse is one of the most extreme examples today, but it reflects a broader global trend.

UNICEF estimates that globally, more than 25 million children of primary age are out of school due to conflict and insecurity.

In wider conflict zones, from Yemen to Sudan, attacks on schools and displacement keep millions from education.

However, Gaza’s situation is exceptional for the scale of destruction, cumulative closure, and overlap with famine, displacement, and repeated bombardment.

The Lost Generation is Not Just a Phrase but a Forecast

Researchers warn that, unless things change, Gaza’s children will not simply “catch up.” They will represent a generation with permanent educational loss, with consequences echoing for decades.

This is the core of the Cambridge study’s warning:

“Children in Gaza will have lost the equivalent of five years’ worth of education… and many will be a full decade behind their educational level.”

Even temporary or online learning measures introduced by UNRWA and the Palestinian Ministry of Education have been severely constrained by destroyed infrastructure, scarce resources, and ongoing insecurity.

Why This Matters Beyond Gaza

When an entire generation loses access to education:

- Entire economies lose future professionals

- Communities lose rebuilding capacity

- Political stability becomes harder to achieve

- Human rights, including dignity and autonomy, are undermined

Gaza’s children are not only Palestinian future workers and citizens. They are part of the global Muslim community, and their loss echoes in every society that values human potential.

Their right to education is universal, and its denial is not a local tragedy but a global failure.

Trending

-

Featured2 years ago

Featured2 years agoWorld passively watching as Israel perpetrates open-ended massacre in Gaza

-

Featured3 years ago

Featured3 years agoArgentina wins the World Cup; are there any other winners?

-

Featured2 years ago

Featured2 years agoIsrael is Hiding Crucial Demographic Facts About Palestinians

-

Featured5 years ago

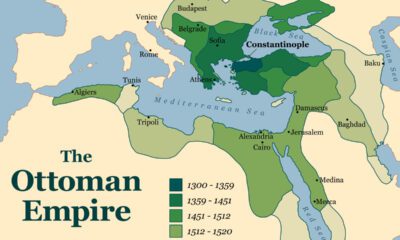

Featured5 years agoHistory of the Ottoman Empire

-

Featured3 years ago

Featured3 years agoChristian militia infiltrate Lebanon

-

Featured5 years ago

Featured5 years ago“Do Not Waste Water Even If You Were at a Running Stream” Prophet Muhammad

-

Featured2 years ago

Featured2 years agoMuhammed: The Greatest Man to walk on Earth

-

Featured3 years ago

Featured3 years agoWorld Leaders Remain Silent Over Human Rights Violations in the UAE